So, I invite you to join me as I try to piece together these reflections—thoughts I’ve held for a long time, now infused with lived experience and practice. My lens is improvisation and movement, tools I’ve explored throughout my life.

Please consider subscribing to this Substack, submitting an application if you’d like me to build a website, or hiring me as a photographer. Also subscribe to my monthly dance and movement event update/ information distribution project undercurrent. In order to stay involved in this work that lights me up from the core, I need to generate more income—and I want to do it through writing and supporting my community. Thank you.

– a

Enjoy the following essay on Resonance in Mutuality.

Resonance in Movement : Mutuality as Collective Power in Non-Hierarchical Communities

Resonance in Movement : Mutuality as Collective Power in Non-Hierarchical Communities

Introduction

Being so close to a devastating climate disaster—and yet untouched—created a dysphoric feeling of relief mixed with a deep responsibility to act. Just 300 miles away, Western North Carolina, a place once considered a climate haven, was struck by the very forces it was thought to evade. This is a region I called home over a decade ago, a community I left without a proper goodbye, a place I believed I would be part of for a long time. When the disaster hit, I felt called, as if drawn by an old bond, to be part of the relief effort.

In response, I joined countless others in mobilizing to help, fueled by the unspoken knowledge of what was unfolding. Together, we worked to get in contact, gather donations, fill cars, make trips, and organize volunteers. The coordination was intense, at times chaotic, but there was something undeniable about it—a kind of resonance in our collective effort. We were connected, not by hierarchy or obligation, but by something more profound. As the urgency settled, systems took shape, and I began to understand the true depth of what we were doing: mutual aid as a force of collective care, real-time community action that attunes individuals to one another and to the environment. This experience left me even more awake to the vital importance of nurturing community as if our lives depend on it—because, in many ways, they do.

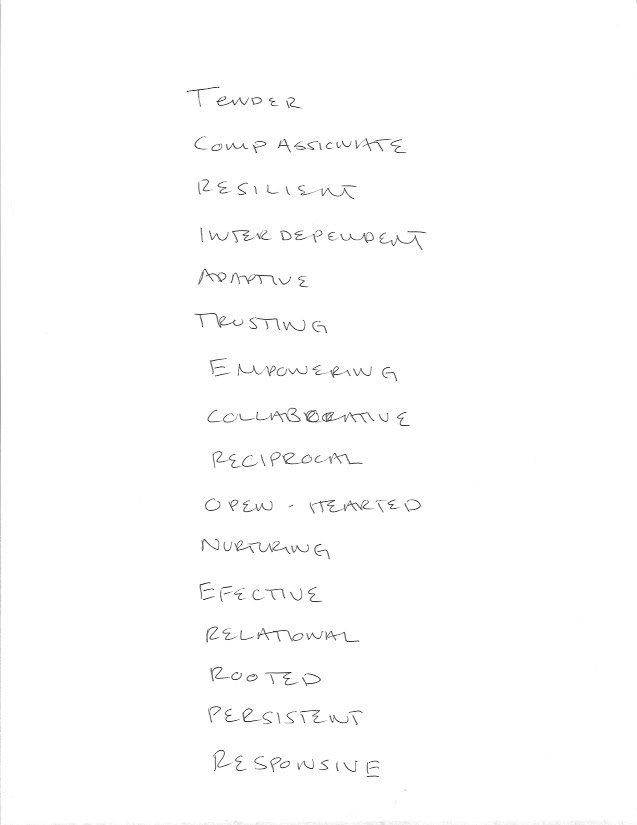

For years, I have explored mutuality through movement research, gravitating toward mutual practices in both improvisation and the distribution of information. In choreography, I’ve worked to build scaffolding for dancers and movers to be autonomous improvisers who sense each other and build movement as a collective unit. In community, I create systems for shared teaching, practice, research, and information exchange, like freeskewl and undercurrent. But in mutual aid, I encountered a form of mutuality rooted in real, urgent need. It is a mutuality that fosters resonance in non-hierarchical structures, where shared energy, mutual understanding, and collective alignment strengthen community bonds and save lives. Here, I explore resonance through the work of Judith Butler, adrienne maree brown, and Susan Sgorbati, whose philosophies on vulnerability, emergent strategy, and natural systems illuminate this powerful experience of collective attunement through mutual aid.

Judith Butler: Resonance Through Vulnerability and Assembly

Judith Butler’s work on collective assembly and vulnerability offers a way of understanding resonance in mutual aid. In Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, Butler argues that when people gather in shared spaces—whether in protest, vigils, or in response to a crisis—they create a form of power rooted in collective vulnerability. Butler’s concept of resonance emerges from the proximity of bodies, the shared recognition of presence and purpose, and the connection that is built without top-down organization.

In the mutual aid effort for Western North Carolina, I witnessed this firsthand. We came together, not because we were directed by a central authority, but because of a shared sense of duty and care. The vulnerability of the moment—the recognition that any of us could be the ones needing aid—created a kind of mutual recognition, a silent bond that made our actions feel powerful and resonant. When individuals gather, each body adds to the collective power through its mere presence, creating a resonance that goes beyond words. This shared focus, an alignment around a common purpose, shifts the collective mindset of a room, deepening a sense of mutual support. Butler would argue that this alignment redefines power as something that emerges from mutuality rather than domination.

Butler’s theory also helps illuminate how non-hierarchical empowerment emerges in these spaces. Within the mutual aid network, leadership did not rest in any one person but shifted fluidly based on the needs of the group. Information, resources, and responsibility circulated among us, empowering each person to act without centralized control. Butler’s concept of emergent power, based on mutual recognition and solidarity, shows how groups working in resonance foster a kind of collective leadership that distributes knowledge and resources freely, building strength without concentrating power.

adrienne maree brown: Emergent Strategy and Nature-Inspired Resilience

adrienne maree brown’s concept of Emergent Strategy draws inspiration from natural systems, focusing on resilience, adaptability, and interdependence. Although resonance is not a term brown frequently uses, the concept is embedded in their idea of shared intention—a palpable energy and synergy that occurs when people align around a common purpose. Brown emphasizes the power of collective focus, suggesting that when groups work with “small is good, small is all,” they create a resonance that amplifies from individual action to collective impact, growing into something much greater than its parts.

Brown encourages communities to be “in right relationship with change,” understanding that adaptability is key to resilience. Just as natural systems respond to changing environments, mutual aid efforts adapt organically to meet immediate needs. Working within mutual aid feels like being part of a living ecosystem. There is a responsiveness and a natural flow to our actions, much like the way natural elements interact and adapt to shifting conditions. In mutual aid, this adaptability allows people to respond fluidly, guided by the needs of the moment rather than by rigid structures. Brown’s vision of decentralized leadership aligns perfectly with this process, suggesting that effective change happens not from the top down but from a place of shared motivation and mutual care.

In Emergent Strategy, brown emphasizes “emergent leadership”—a form of leadership that arises naturally as individuals step forward to meet the needs of the group. This leadership is dynamic, adjusting and shifting as different people bring their skills and energy into alignment with the group’s purpose. Leadership in mutual aid is not held by one individual; it moves fluidly, like energy, emerging as needed and distributing once knowledge and resources are shared among all involved. Brown’s principles of emergent strategy offer a model where power is shared, not held, reinforcing a non-hierarchical empowerment that resonates deeply within the community.

Susan Sgorbati: Emergent Improvisation and Embodying Natural Systems

Susan Sgorbati’s Emergent Improvisation integrates dance and complex systems science to explore the principles of natural adaptation, responsiveness, and relationality in movement. Sgorbati’s work highlights how principles observed in ecosystems—such as adaptability, mutual influence, and interconnectedness—can be mirrored in human movement practices. By observing and embodying these complex patterns, dancers mirror natural processes, creating a sense of resonance within the group—a unified rhythm or energy that emerges collectively, rather than from any single individual directing the movement.

In emergent improvisation, resonance is an emergent quality arising from dancers’ mutual awareness and responsiveness to one another. Sgorbati describes how dancers “attune” to each other, creating a resonant energy that is palpable both for the performers and the audience. This attunement mirrors the alignment felt within mutual aid efforts, where individuals come together and respond to one another’s needs, creating a collective strength rooted in shared focus and adaptability. Resonance, while supported by individual contributions, is ultimately a product of the group’s synchronized intentions and actions, a harmony that feels “alive” in real time.

Just as in emergent improvisation, resonance in mutual aid extends beyond those directly involved. The community itself becomes an active participant, contributing to and receiving from the resonant field of mutual support. The effects of mutual aid radiate outward, impacting the broader community, which often engages directly through donations, volunteering, or simply witnessing the collective action. In this way, the resonant energy is translated and felt by the perceiver—the audience of the community itself—reinforcing the sense of shared purpose and interconnectedness that underpins mutual aid.

Conclusion: Resonance as Collective Power in Mutual Aid

Through the perspectives of Butler, brown, and Sgorbati, mutual aid reveals itself as more than just an emergency response; it is a living expression of resonance, a non-hierarchical structure rooted in collective empowerment. Each of these thinkers illuminates an aspect of mutual aid’s transformative power: Butler’s resonance through vulnerability and assembly, brown’s emergent strategy and adaptability, and Sgorbati’s natural system-inspired improvisation. Together, they offer a vision of mutual aid as a force that brings people together in response to both immediate needs and shared values.

This experience has shifted my understanding of mutual aid from theory to a deeply embodied practice. It is a practice that depends on connection, responsiveness, and a willingness to show up in vulnerability. Mutual aid, like dance, is an art of resonance, a composition of care—a way of aligning with others to create something greater than any one person alone. In this alignment, I have found a kind of power, a sense of purpose that is both personal and collective. And it has left me with a question for those reading: How might we each nurture the resonant, mutual connections in our own lives, creating communities that sustain us in times of crisis and beyond?

If you are interested in seeing how this translates into my composition and choreography, here is a link to my Thesis work called Good Grief, made in 2019.

mhmm thank you for this beautiful synthesis of your work this past month. I can feel the pulse of praxis, weaving theory and action. more please